John Ruskin: A prophet for our troubled times

In 1964, Kenneth Clark set out the problems of loving John Ruskin. One was his fame itself. Like his sometime pupil Oscar Wilde (who, along with other of his Oxford students he persuaded to dig a road in Hinksey in order that they learn the dignity of labour), Ruskin defined the art and culture of his century. “For almost 50 years,” Clark wrote in his book, Ruskin Today, “to read Ruskin was accepted as proof of the possession of a soul.” Gladstone would have made him poet laureate “and was only prevented from doing so by the fact that [Ruskin] was out of his mind”.

Ruskin was a man who believed in angels but championed the most radical British artist of his time. He was a social reformer and utopian who was at heart a conservative reactionary and a puritan. He was a brilliant artist who ought to have been a bishop. He hated trains but invented the blog.

How can it be that a man so celebrated in his time is only fitfully remembered now, 200 years after his birth – and then mostly for a salacious story that he was too intimidated by the sight of his young wife’s pubic hair to perform on his wedding night? He’s a beardy Victorian worthy, preserved in sepia photographs and unread books with inexplicable titles – Unto This Last, Sesame and Lilies, Praeterita – consigned to the top shelves of charity shops.

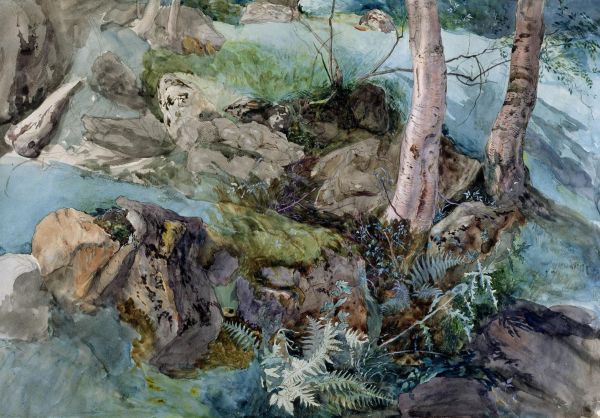

The problem lies in the fact that Ruskin rejects all those presumptions even in his own lifetime. His watercolours of the natural world – from mosses to Swiss mountains – are astonishing, hyper-real representations of something close to his soul, a metaphysical reality. He declined to join the headlong rush of economic progress and rejected the mores of his class. In the famous portrait of him by John Everett Millais – the Pre-Raphaelite artist who, even as he painted the picture in the Scottish Highlands, was about to seduce Ruskin’s young wife, Effie Gray – he stands on a rock by a waterfall, as if dominating the terrain around him. He looks the picture of Victorian rectitude; but he was undermining the century with his crusade.

His first offence was to champion William Turner’s paintings. Almost intuitively, Ruskin understood the power of what Turner was trying to do. As the contemporary eco-philosopher Timothy Morton says, “art is from the future”; Ruskin saw that futurity in Turner. His second offence was to attack capitalism. As Clark notes, Tolstoy, Gandhi and Bernard Shaw thought him one of the greatest social reformers of his time. When members at the first meeting of the Parliamentary Labour Party were asked which book had most influenced them, they answered Ruskin’s Unto This Last. Bernard Shaw pithily summed up Ruskin’s affront to his own class: he told them, “You are a parcel of thieves.” [Continue reading…]