China-backed Sumatran dam threatens the rarest ape in the world

By Bill Laurance, James Cook University

The plan to build a massive hydropower dam in Sumatra as part of China’s immense Belt and Road Initiative threatens the habitat of the rarest ape in the world, which has only 800 remaining members.

This is merely the beginning of an avalanche of environmental crises and broader social and economic risks that will be provoked by the BRI scheme.

Read more:

How we discovered a new species of orangutan in northern Sumatra

The orangutan’s story began in November 2017, when scientists made a stunning announcement: they had discovered a seventh species of Great Ape, called the Tapanuli Orangutan, in a remote corner of Sumatra, Indonesia.

In an article published in Current Biology today, my colleagues and I show that this ape is perilously close to extinction – and that a Chinese-sponsored megaproject could be the final nail in its coffin.

Sumatran Orangutan Society

Ambitious but ‘nightmarishly complicated’

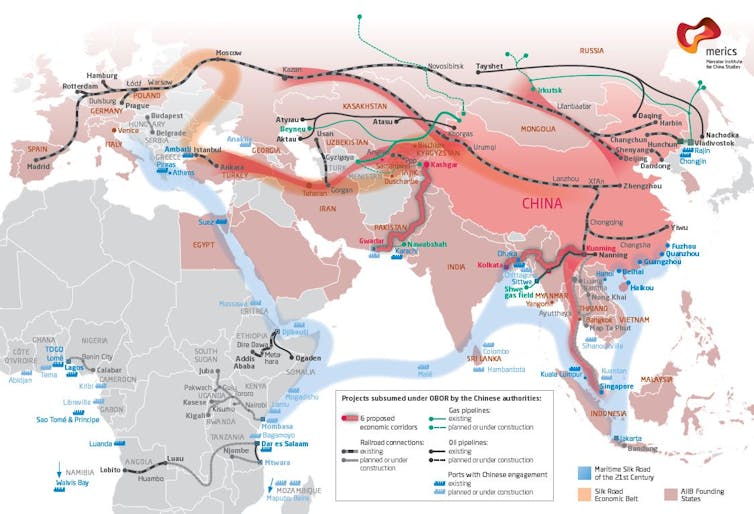

The BRI is an ambitious but nightmarishly complicated venture, and far less organised than many believe. The hundreds of road, port, rail, and energy projects will ultimately span some 70 nations across Asia, Africa, Europe and the Pacific region. It will link those nations economically and often geopolitically to China, while catalysing sweeping expansion of land-use and extractive industries, and will have myriad knock-on effects.

Up to 2015, the hundreds of BRI projects were reviewed by the powerful National Development and Reform Commission, which is directly under China’s State Council. Many observers have assumed that the NDRC will help coordinate the projects, but the only real leverage they have is over projects funded by the big Chinese policy banks – the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China – which they directly control.

Mercator Institute for China Studies

Most big projects – many of which are cross-national – will have a mix of funding from various sources and nations, meaning that no single entity will be in charge or ultimately responsible. An informed colleague in China describes this model as “anarchy”.

Tapanuli Orangutan

The dangerous potential of the BRI becomes apparent when one examines the Tapanuli Orangutan. With fewer than 800 individuals, it is one of the rarest animals on Earth. It survives in just a speck of rainforest, less than a tenth the size of Sydney, that is being eroded by illegal deforestation, logging, and poaching.

All of these threats propagate around roads. When a new road appears, the ape usually disappears, along with many other rare species sharing its habitat, such as Hornbills and the endangered Sumatran Tiger.

Maxime Aliaga

The most imminent threat to the ape is a US$1.6 billion hydropower project that Sinohydro (China’s state-owned hydroelectric corporation) intends to build with funding from the Bank of China and other Chinese financiers. If the project proceeds as planned, it will flood the heart of the ape’s habitat and crisscross the remainder with many new roads and powerline clearings.

It’s a recipe for ecological Armageddon for one of our closest living relatives. Other major lenders such as the World Bank and Asian Development Bank aren’t touching the project, but that isn’t slowing down China’s developers.

What environmental safeguards?

China has produced a small flood of documents describing sustainable lending principles for its banks and broad environmental and social safeguards for the BRI, but I believe many of these documents are mere paper tigers or “greenwashing” designed to quell anxieties.

According to insiders, a heated debate in Beijing right now revolves around eco-safeguards for the BRI. Big corporations (with international ambitions and assets that overseas courts can confiscate) want clear guidelines to minimise their liability. Smaller companies, of which there are many, want the weakest standards possible.

The argument isn’t settled yet, but it’s clear that the Chinese government doesn’t want to exclude its thousands of smaller companies from the potential BRI riches. Most likely, it will do what it has in the past: issue lofty guidelines that a few Chinese companies will attempt to abide by, but that most will ignore.

Stacked deck

There are three alarming realities about China, of special relevance to the BRI.

First, China’s explosive economic growth has arisen from giving its overseas corporations and financiers enormous freedom. Opportunism, graft and corruption are embedded, and they are unlikely to yield economically, socially or environmentally equitable development for their host nations. I detailed many of these specifics in an article published by Yale University last year.

Second, China is experiencing a perfect storm of trends that ensures the harsher realities of the BRI are not publicly aired or even understood in China. China has a notoriously closed domestic media – ranked near the bottom in press freedom globally – that is intolerant of government criticism.

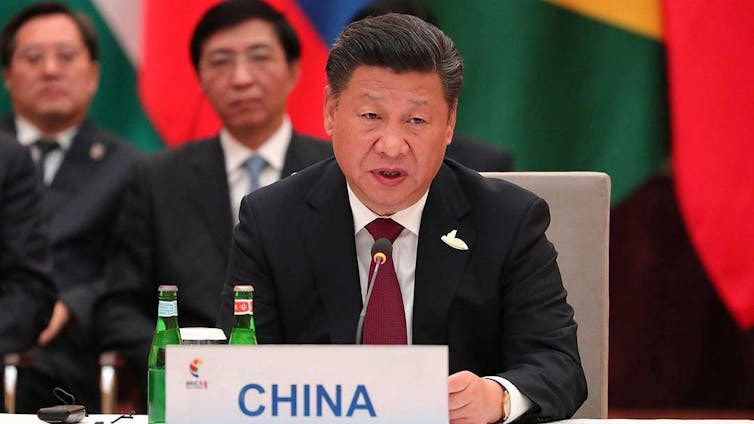

Beyond this, the BRI is the signature enterprise of President Xi Jinping, who has become the de-facto ruler of China for life. Thanks to President Xi, the BRI is now formally enshrined in the constitution of China’s Communist Party, making it a crime for any Chinese national to criticise the program. This has had an obvious chilling effect on public discourse. Indeed, I have had Chinese colleagues withdraw as coauthors of scientific papers that were even mildly critical of the BRI.

Foreign Policy Journal

Third, China is becoming increasingly heavy-handed internationally, willing to overtly bully or covertly pull strings to achieve its objectives. Professor Clive Hamilton of Charles Sturt University has warned that Australia has become a target for Chinese attempts to stifle criticism.

Remember the ape

It is time for a clarion call for greater caution. While led by China, the BRI will also involve large financial commitments from more than 60 nations that are parties to the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, including Australia and many other Western nations.

Read more:

China’s growing footprint on the globe threatens to trample the natural world

![]() We all have a giant stake in the Belt and Road Initiative. It will bring sizeable economic gains for some, but in nearly 40 years of working internationally, I have never seen a program that raises more red flags.

We all have a giant stake in the Belt and Road Initiative. It will bring sizeable economic gains for some, but in nearly 40 years of working internationally, I have never seen a program that raises more red flags.

Bill Laurance, Distinguished Research Professor and Australian Laureate, James Cook University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.