Some Neanderthals hunted bigger animals, across a larger range, than modern humans

Chettaprin.P / Shutterstock

By Bethan Linscott, University of Oxford

The region of Estremadura in Portugal was home to a band of Neanderthals – an ancient evolutionary relative of modern humans – about 95,000 years ago. They made use of the patchwork of limestone caves, crags and river valleys, leaving traces of their activities in the form of stone tools, butchered animal bones and the remnants of fireplaces.

Now their teeth are providing new insights on how they hunted and interacted with their landscape. I was one of an international team of researchers that compared the levels of different forms of the chemical element strontium that had been preserved within the tooth enamel of two Neanderthals from the Almonda cave system in central Portugal, dating back about 95,000 years. The results have been published in the journal PNAS.

We also analysed the tooth enamel of a human who lived about 13,000 years ago during what’s known as the Magdalenian period, between about 17,000 and 12,000 years ago. Coupled with data recovered from the tooth enamel of a variety of local animals –- including horse, wild goat, red deer and an extinct form of rhinoceros –- our findings show that Neanderthals in the region were hunting fairly large animals across wide tracts of land. Humans living in the same location tens of thousands of years later survived on smaller creatures in an area half the size.

Some researchers have wondered whether differences between the subsistence strategies of modern humans and Neanderthals contributed to the disappearance of the latter around 40,000 years ago. Our study was conducted over a limited area, but wider evidence suggests that range size and prey type may well have varied between different regions.

From rocks to enamel

Isotopes of the element strontium in rocks gradually change over millions of years because of radioactive processes. This means they vary from place to place depending on the age of the underlying geology. As rocks weather, these isotopic “fingerprints” are passed into plants via sediments and make their way along the food chain –- eventually passing into tooth enamel.

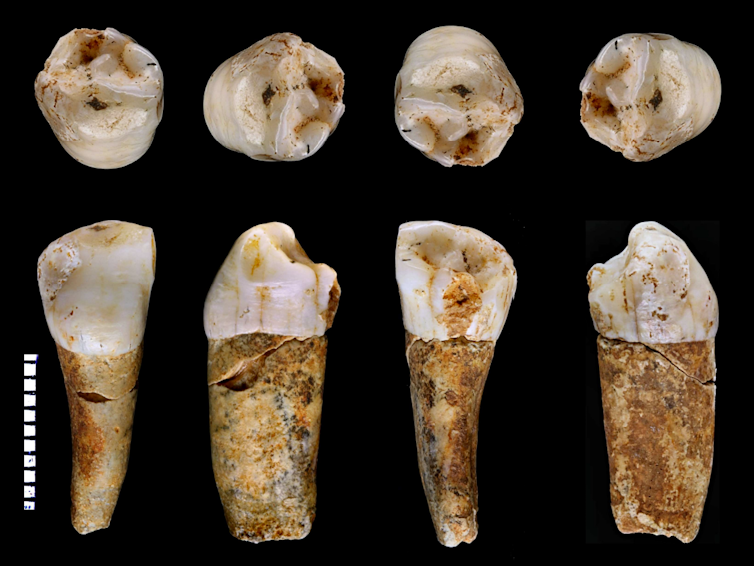

Because tooth enamel forms incrementally, it preserves a times series of those strontium isotope signals, which in turn reflect the geological origin of the food a person or animal ate over time. Using a technique for analysing elements in archaeological samples, we were able to take thousands of strontium isotope measurements along the length of the tooth enamel, measuring variation over the two or three years it takes for the enamel to form.

Credit: João Zilhão, Author provided

By comparing the strontium isotopes in the teeth with sediments collected at different locations in the region, we were able to reconstruct the movements of Neanderthals and the Magdalenian human across the landscape. The geology around the Almonda caves is highly variable, making it possible to spot mobility of just a few kilometres.

We also looked at isotopes in the tooth enamel of animals found in the cave system. Alongside strontium, we measured oxygen isotopes, which vary seasonally from summer to winter. This enabled us to establish not only where the animals ranged across the landscape, but in which seasons they were available for hunting.

Seasonal patterns

We showed that the Neanderthals, who were targeting large animals, could have hunted wild goat in the summer, whereas horses, red deer and an extinct form of rhinoceros were available all year round within about 30km of the cave. The Magdalenian human showed a different pattern of subsistence, with seasonal movement of about 20km from the Almonda caves to the banks of the Tagus River, and a diet that included rabbits, red deer, wild goat and freshwater fish.

We approximated the territory of the two different human groups, revealing contrasting results. The Neanderthals obtained their food over approximately 600 sq km, whereas the humans occupied a much smaller territory of about 300 sq km. They suggest that the reduction in territory size could be a shift in population density.

With a relatively low population, Neanderthals were free to roam further to target large prey species, such as horses, without encountering rival groups. By the Magdalenian period, an increase in population density reduced available territory, and human groups had moved down the food chain to occupy smaller territories, hunting mostly rabbits and catching fish on a seasonal basis.

The study illustrates how new analytical methods can deepen our understanding of archaeology and human evolution. Previously, our knowledge of the lives and behaviour of past individuals was limited to what we could infer from marks on their bones or the artefacts they used. Now, using the chemistry of bones and teeth, we can begin to reconstruct detailed individual life histories, even as far back as the Neanderthals.![]()

Bethan Linscott, Postdoctoral Researcher, Archaeological Geochemistry, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.