Russian troops fought for control of a nuclear power plant in Ukraine – a safety expert explains how warfare and nuclear power are a volatile combination

AP Photo/Lisa Leutner

By Najmedin Meshkati, University of Southern California

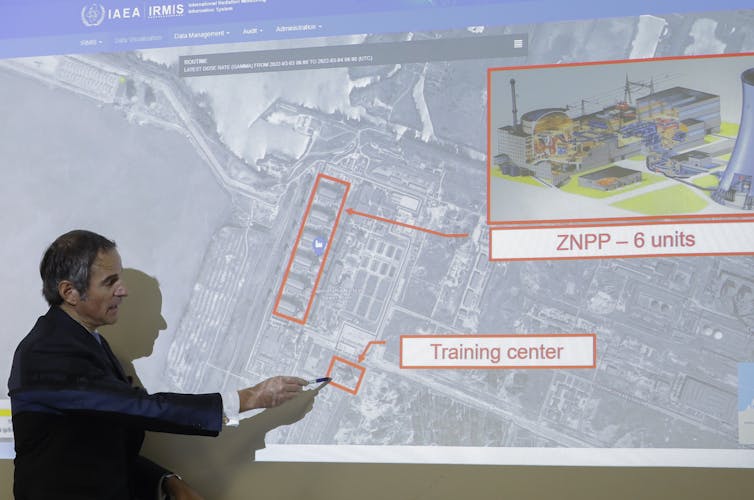

Russian forces have taken control of Europe’s largest nuclear power plant after shelling the Zaporizhzhia facility in the Ukrainian city of Enerhodar.

The overnight assault caused a blaze at the facility, prompting fears over the safety of the plant and evoking painful memories in a country still scarred by the world’s worst nuclear accident, at Chernobyl in 1986. The site of that disaster is also under Russian control as of Feb. 24, 2022.

On March 4, Ukrainian authorities reported to the International Atomic Energy Agency that the fire at Zaporizhzhia had been extinguished and that Ukrainian employees were reportedly operating the plant under Russian orders. But safety concerns remain.

The Conversation asked Najmedin Meshkati, a professor and nuclear safety expert at the University of Southern California, to explain the risks of warfare taking place in and around nuclear power plants.

How safe was the Zaporizhzhia power plant before the Russian attack?

The facility at Zaporizhzhia is the largest nuclear plant in Europe, and one of the largest in the world. It has six pressurized water reactors, which use water to both sustain the fission reaction and cool the reactor. These differ from the reaktor bolshoy moshchnosty kanalny reactors at Chernobyl, which used graphite instead of water to sustain the fission reaction. RBMK reactors are not seen as very safe, and there are only eight remaining in use in the world, all in Russia.

The reactors at Zaporizhzhia are of moderately good design. And the plant has a decent safety record, with a good operating background.

Ukraine authorities tried to keep the war away from the site by asking Russia to observe a 30-kilometer safety buffer. But Russian troops surrounded the facility and then seized it.

What are the risks to a nuclear plant in a conflict zone?

Nuclear power plants are built for peacetime operations, not wars.

The worst thing that could happen is if a site is deliberately or accidentally shelled and the containment building – which houses the nuclear reactor – is hit. These containment buildings are not designed or built for deliberate shelling. They are built to withstand a minor internal explosion of, say, a pressurized water pipe. But they are not designed to withstand a huge explosion.

It is not known whether the Russian forces deliberately shelled the Zaporizhzhia plant. It may have been inadvertent, caused by a stray missile. But we do know they wanted to capture the plant.

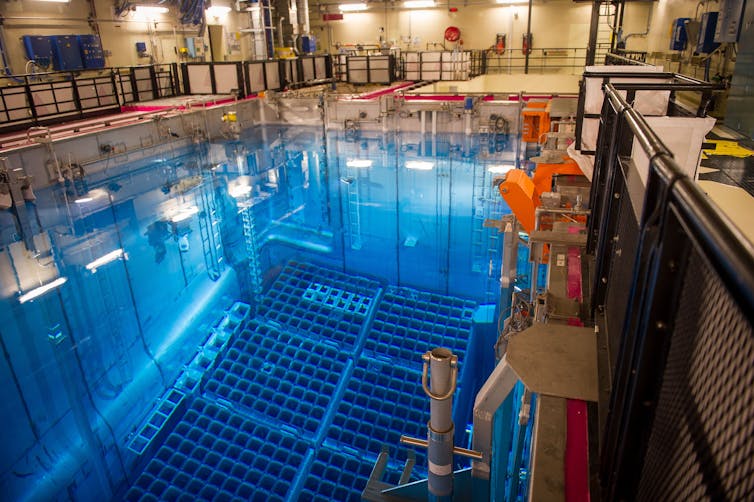

If a shell hit the plant’s spent fuel pool – which contains the still-radioactive spent fuel – or if fire spread to the spent fuel pool, it could release radiation. This spent fuel pool isn’t in the containment building, and as such is more vulnerable.

As to the reactors in the containment building, it depends on the weapons being used. The worst-case scenario is that a bunker-buster missile breaches the containment dome – consisting of a thick shell of reinforced concrete on top of the reactor – and explodes. That would badly damage the nuclear reactor and release radiation into the atmosphere. And because of any resulting fire, sending in firefighters would be difficult. It could be another Chernobyl.

What are the concerns going forward?

The biggest worry was not the fire at the facility. That did not affect the containment buildings and has been extinguished.

The safety problems I see now are twofold:

1) Human error

The workers at the facility are now working under incredible stress, reportedly at gunpoint. Stress increases the chance of error and poor performance.

One concern is that the workers will not be allowed to change shifts, meaning longer hours and tiredness. We know that a few days ago at Chernobyl, after the Russians took control of the site, they did not allow employees – who usually work in three shifts – to swap out. Instead, they took some workers hostage and didn’t allow the other workers to attend their shifts.

At Zaporizhzhia we may see the same.

There is a human element in running a nuclear power plant – operators are the first and last layers of defense for the facility and the public. They are the first people to detect any anomaly and to stop any incident. Or if there’s an accident, they will be the first to heroically try to contain it.

2) Power failure

The second problem is that the nuclear plant needs constant electricity, and that is harder to maintain in wartime.

Even if you shut down the reactors, the plant will need off-site power to run the huge cooling system to remove the residual heat in the reactor and bring it to what is called a “cold shutdown.” Water circulation is always needed to make sure the spent fuel doesn’t overheat.

Spent fuel pools also need constant circulation of water to keep them cool. And they need cooling for several years before being put in dry casks. One of the problems in the 2011 Fukushima disaster in Japan was the emergency generators, which replaced lost off-site power, got inundated with water and failed. In situations like that you get “station blackout” – and that is one of the worst things that could happen. It means no electricity to run the cooling system.

Guillaume Souvant/AFP via Getty Images

In that circumstance, the spent fuel overheats and its zirconium cladding can cause hydrogen bubbles. If you can’t vent these bubbles they will explode, spreading radiation.

If there is a loss of outside power, operators will have to rely on emergency generators. But emergency generators are huge machines – finicky, unreliable gas guzzlers. And you still need cooling waters for the generators themselves.

My biggest worry is that Ukraine suffers from a sustained power grid failure. The likelihood of this increases during a conflict, because pylons may come down under shelling or gas power plants might get damaged and cease to operate. And it is unlikely that Russian troops themselves will have fuel to keep these emergency generators going – they don’t seem to have enough fuel to run their own personnel carriers.

How else does a war affect the safety of nuclear plants?

One of the overarching concerns is that war degrades safety culture, which is crucial in running a plant. I believe that safety culture is analogous to the human body’s immune system, which protects against pathogens and diseases; and because of the pervasive nature of safety culture and its widespread impact, according to psychologist James Reason, “it can affect all elements in a system for good or ill.”

It is incumbent upon the leadership of the plant to strive for immunizing, protecting, maintaining and nurturing the healthy safety culture of the nuclear plant.

War adversely affects the safety culture in a number of ways. Operators are stressed and fatigued and may be scared to death to speak out if something is going wrong. Then there is the maintenance of a plant, which may be compromised by lack of staff or unavailability of spare parts. Governance, regulation and oversight – all crucial for the safe running of a nuclear industry – are also disrupted, as is local infrastructure, such as the capability of local firefighters. In normal times you might have been able to extinguish the fire at Zaporizhzhia in five minutes. But in war, everything is harder.

So what can be done to better protect Ukraine’s nuclear power plants?

This is an unprecedented and volatile situation. The only solution is a no-fight zone around nuclear plants. War, in my opinion, is the worst enemy of nuclear safety.

[Over 150,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletters to understand the world. Sign up today.]![]()

Najmedin Meshkati, Professor of Engineering and International Relations, University of Southern California

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.