Breaking up families? America looks like a Dickens novel

Department of Health and Human Services

By Sarah Bilston, Trinity College

The news has been full these past few weeks of disturbing stories from the nation’s borders. The Trump administration has separated immigrant children from their parents precisely to discourage others from trying to enter the country.

Trump has signed an order to end the practice. But thousands of children have been traumatized as part of an explicit effort to, in Attorney General Jeff Sessions’s words, send a powerful “message” to other potential immigrants. Sessions used the Bible to defend the practice: “I would cite to you the Apostle Paul and his clear and wise command in Romans 13 to obey the laws of the government because God has ordained them for the purpose of order.”

Public domain

What has struck me, as a professor of English literature, are the startling parallels between the Trump administration’s policy on immigrant families and the “New” Poor Laws of England in the 1830s, whose cruelty was illuminated by Charles Dickens in novels and other writings.

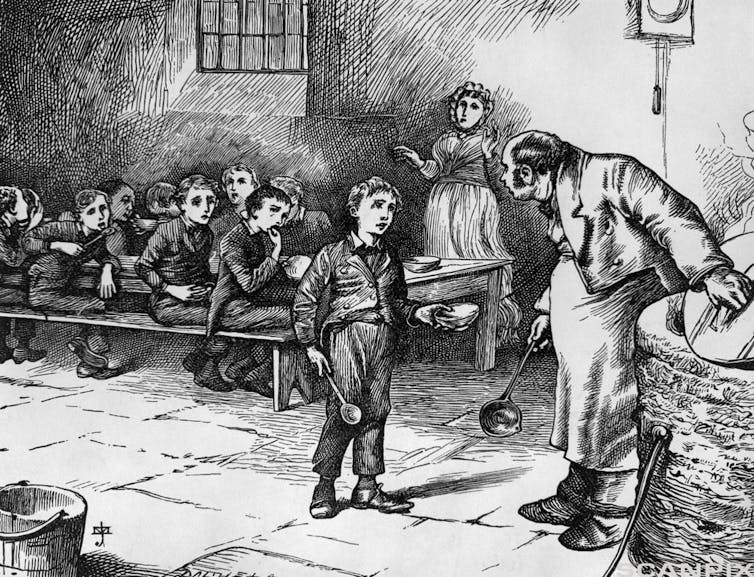

England tried much the same kind of tactics that Trump’s administration has used. Americans may remember the suffering face of Oliver Twist, begging for just a little more food. It may surprise some to realize that Dickens wrote the novel specifically to shine a light on new and brutal laws. Dickens was particularly concerned by the state’s assault on the integrity of the family.

‘Fraud, indolence or improvidence’

England’s “New” Poor Laws of the 1830s were designed to “solve” what was believed to be a common problem: the existence of a body of weak, lazy people leeching off the state. How could the government end abuses of the system? How could money be saved, diverted back to the honest hard-working citizens who paid their way?

In 1834, a Royal Commission issued a report insisting that poverty was almost always a result of “fraud, indolence or improvidence.” Good news: This, apparently, could be fixed.

The commission rolled out a series of recommendations. At the center of these was a core idea: The poor should be cared for in conditions so abject, so truly humiliating, only the really desperate would turn to them.

Under the “workhouse test,” relief would only be given to those willing to relinquish their independence, their human dignity, their spouses and their children. Others, the argument went, would buck up, get a job and stop bothering the righteous rest. Their rights, needs and humanity were disregarded.

The new rules went into effect on June 1, 1835, two years before Victoria became queen.

Families torn apart

Children forced into the workhouse system were either housed in separate buildings from their parents or sent miles away, to live in government-run district schools. The “reformers” proudly trumpeted that children could be fed less than adults when families were separated. They also argued children would learn new and better values once isolated from their parents.

Many families were never reunited.

Dickens was appalled. “Oliver Twist” exposes, on every page, the hypocrisy of those who brutalize vulnerable children and claim to be virtuous in the process.

AP/New York Public Library

In an early scene, Oliver sobs when the Board of the Workhouse condemns him because he does not know how to pray. Oliver has never been taught to pray – has never been shown kindness, sympathy or compassion of any kind.

“What a noble illustration of the tender laws of this favored country,” Dickens remarks bitterly, as Oliver weeps himself into unconsciousness. “They let the paupers go to sleep!”

In later novels, Dickens continued to expose the hypocrisy of those in power. He particularly loathed all those who used Christianity as a “constable’s staff.”

“Bleak House”’s horrific Mrs. Pardiggle is, as Dickens put it, an “inexorable moral Policeman.” She shouts Christian teachings at the poor and suffering and fails in her most basic duties of care. She’s so busy spouting religious text, she does not notice when a baby dies in front of her.

Dickens was not the only writer to expose the horrors of the poor laws. The separation of children from their parents was a flashpoint then, as now.

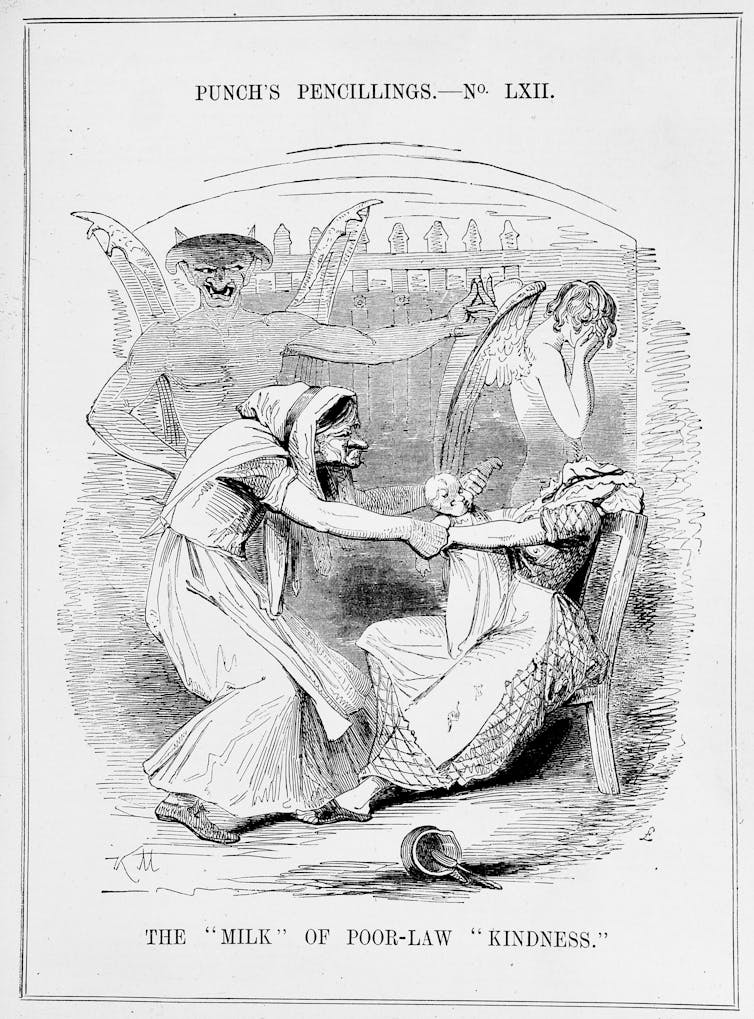

A famous 1843 cartoon in Punch, called “The Milk of Poor-Law ‘Kindness,’” was the Victorian equivalent of the recent photo of a sobbing two-year-old by her immigrant mother’s knees. It showed a crone-like workhouse matron dragging a baby from its horrified mother, as a devil sneers and an angel hides its face in horror.

public doman

Marches and acts of political disobedience followed, including riots and arson against the new-built workhouses, with many Victorians uniting around the sanctity of the family.

The depiction of paupers as suffering people, not just leeches on the system, helped shock the population and precipitate social change. With deliberate use of sentiment and tear-jerking scenes of tragedy and loss, Charles Dickens gave a human face to those who were being treated with profound inhumanity.

I’ve taught the novels of Charles Dickens for more than 20 years. My students have tended to approach his era as a bizarre and strangely cruel period in human history. But Dickens’s world has come to life again. Our government has detained children as young as infants in “tender age” centers in south Texas.

![]() It’s 2018, but it sure feels like 1834.

It’s 2018, but it sure feels like 1834.

Sarah Bilston, Associate Professor of English, Trinity College

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.