Exxon, Apple and other corporate giants will have to disclose all their emissions under California’s new climate laws – that will have a global impact

David McNew/Getty Images

By Lily Hsueh, Arizona State University

Many of the world’s largest public and private companies will soon be required to track and report almost all of their greenhouse gas emissions if they do business in California – including emissions from their supply chains, business travel, employees’ commutes and the way customers use their products.

That means oil and gas companies like Chevron will likely have to account for emissions from vehicles that use their gasoline, and Apple will have to account for materials that go into iPhones.

It’s a huge leap from current federal and state reporting requirements, which require reporting of only certain emissions from companies’ direct operations. And it will have global ramifications.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed two new rules into law on Oct. 7, 2023. Under the new Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act, U.S.- companies with annual revenues of US$1 billion or more will have to report both their direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions starting in 2026 and 2027. The California Chamber of Commerce opposed the regulation, arguing it would increase companies’ costs. But more than a dozen major corporations endorsed the rule, including Microsoft, Apple, Salesforce and Patagonia.

The second law, the Climate-Related Financial Risk Act, requires companies generating $500 million or more to report their financial risks related to climate change and their plans for risk mitigation.

As a professor of economics and public policy, I study corporate environmental behavior and public policy, including whether disclosure laws like these work to reduce emissions. I believe California’s new rules represent a significant step toward mainstreaming corporate climate disclosures and potentially meaningful corporate climate actions.

Many big corporations are already reporting

Most of the companies covered by California’s climate disclosure rules are multinational corporations. They include technology companies such as Apple, Google and Microsoft; giant retailers like Walmart and Costco; and oil and gas companies such as ExxonMobil and Chevron.

Many of these large corporations have been preparing for mandatory disclosure rules for several years.

Close to two-thirds of the companies listed in the S&P 500 index voluntarily report to CDP, formerly called the Carbon Disclosure Project. CDP is a nonprofit that surveys companies on behalf of institutional investors about their carbon management and plans to reduce carbon emissions.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Many of them also face reporting requirements elsewhere, including in the European Union, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Singapore and cities like Hong Kong.

Moreover, some of the same U.S. companies, notably banks and asset managers that operate or sell products in Europe, have already started to comply with the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation. Those regulations require companies to report how sustainability risks are integrated into investment decision-making.

While California isn’t the first place to mandate climate disclosures, it is the fifth-largest economy in the world. So, the state’s new laws are poised to have substantial influence worldwide. Subsidiaries of companies that didn’t have to report their emissions before will now be subject to disclosure requirements. California is in effect exercising its immense market leverage to establish climate disclosures as standard practice in the U.S. and beyond.

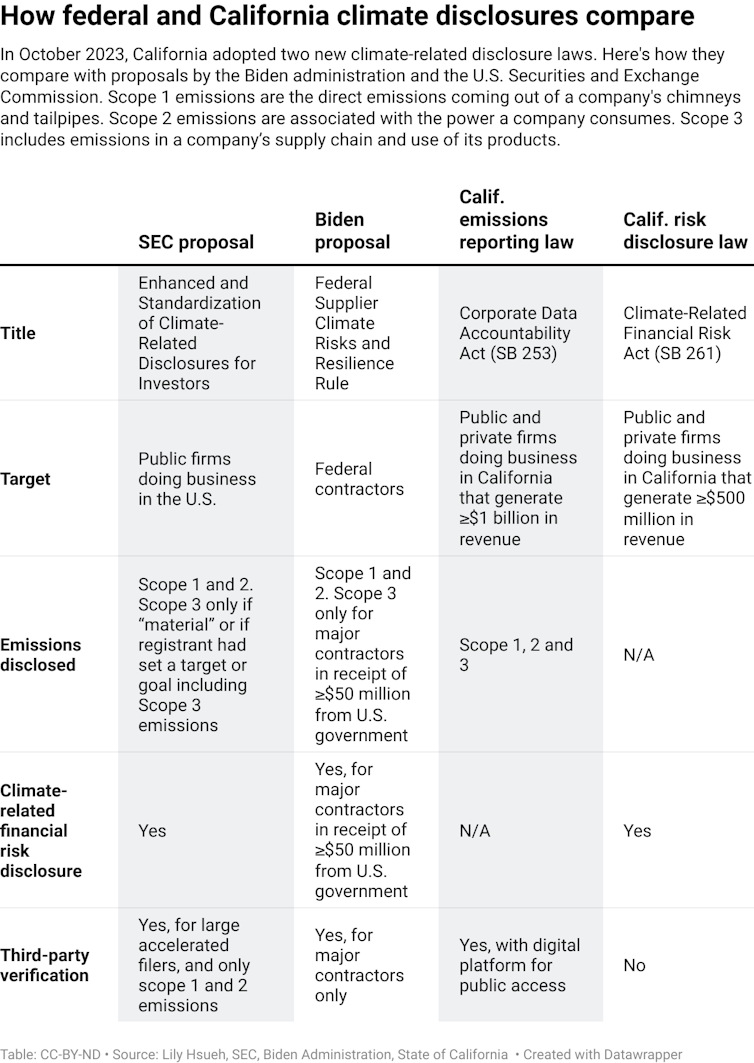

California also has a history of being a test bed for future federal U.S. policies. The U.S. government is considering broader emissions reporting requirements. But California’s new rules go further than either the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s proposed corporate climate disclosure rules or President Joe Biden’s proposed disclosure rules for federal contractors.

The most controversial part of the new disclosure rules involves scope 3 emissions. These are emissions from a company’s suppliers and its consumers’ use of its products, and they are notoriously difficult to track accurately.

California’s new emissions reporting law directs the California Air Resources Board, which will develop the regulations and administer them, to allow some leeway in scope 3 reporting as long as the reports are made with a reasonable basis and disclosed in good faith. It’s also important to note that at this point the disclosure laws don’t require companies to cut these emissions, only to report them. But tracking scope 3 emissions does highlight where companies could pressure suppliers to make changes.

What can disclosures achieve?

The plethora of climate disclosure mandates globally suggest that policymakers and investors around the world perceive climate disclosures as driving actions that protect the environment. The big question is: Do disclosure rules actually work to reduce emissions?

My research shows that voluntary carbon disclosure systems like CDP’s that focus on reporting corporate sustainability outputs, such as having science-based emissions targets, tend not to be as effective as those that focus on outcomes, such as a company’s actual carbon emissions.

For example, a company could earn an A or B grade from CDP and still increase its entitywide carbon emissions, notably when it does not face regulatory pressure.

In contrast, a recent study of the U.K.’s 2013 disclosure mandate for U.K.-incorporated listed firms found that companies reduced their operational emissions by about 8% relative to a control group, with no significant changes to their profitability. When companies report their emissions, they can gain important knowledge about inefficiencies in their operations and supply chains that weren’t evident before.

Ultimately, a well-designed disclosure program, whether voluntary or mandatory, needs to focus on consistency, comparability and accountability. Those traits allow companies to demonstrate that their climate pledges and actions are real and not just a front for greenwashing.![]()

Lily Hsueh, Associate Professor of Economics and Public Policy, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.