Cahokian culture spread across eastern North America 1,000 years ago in an early example of diaspora

JByard/iStock via Getty Images Plus

By Jayur Mehta, Florida State University

An expansive city flourished almost a thousand years ago in the bottomlands of the Mississippi River across the water from where St. Louis, Missouri stands today. It was one of the greatest pre-Columbian cities constructed north of the Aztec city of Tenochititlan, at present-day Mexico City.

The people who lived in this now largely forgotten city were part of a monument-building, corn-farming culture. No one knows what its inhabitants named this place, but today archaeologists call the city Cahokia.

Excavations show it was home to thousands of families. The city held hundreds of earthen mounds that supported council houses, homes for social elites, tombs for powerful leaders and reminders of lunar alignments. In addition, archaeologists have discovered a Woodhenge at Cahokia – a circular celestial observatory made of large wooden posts.

Keith Ashley, CC BY-ND

Archaeologists call the pre-Columbian societies that lived in the Mississippi River Valley region “Mississippian cultures.” These people stretched as far west as Oklahoma, north to Wisconsin, south to Mississippi and Louisiana, and east to Florida and North Carolina. Though broadly similar, it’s unlikely these people thought of themselves as a unified political body.

A complex question in American archaeology hinges on how these cultures arose and the ways in which they shared ideas, goods and people.

Did the Cahokians create Mississippian culture as they moved outward from their homeland, bringing their artifacts and ideas with them? Or did Cahokians spread across the Midwest and Southeast, meeting new communities and sharing ideas along the way, eventually helping form Mississippian culture through a kind of melting-pot process? Recently, my colleagues Sarah Baires, Melissa Baltus and Elizabeth Watts Malouchos and I have contributed to new research investigating what it meant to be a Cahokian and Mississippian.

Jayur Mehta, CC BY-ND

Striking out from Cahokia

Like cities today, Cahokia was a diverse place inhabited by groups of people with different histories, diverging values and varying ideas. So when people left the city, they likely had a variety of reasons.

Early in Cahokia’s history, movements into and out of the city may have been tied to religious gatherings while later migrations out of the city may have been related to political change. While there is some evidence for conflict and potential for drought in the region, archaeologists have no conclusive evidence that those were the ultimate causes for people leaving the city. After all, some people continued to live there.

Whatever their motives, as Cahokian citizens spread out from St. Louis and migrated throughout the woodlands east of the Mississippi River, they carried their culture with them. Sometimes these were unique artifacts, like particular ceramics typical of their region. But they also brought with them specific cultural constructs, like their beliefs in the ordering of the cosmos and relationships between the upper and lower worlds.

Recreating parts of home

During the early days of Cahokia, around 1050, emissaries from the city traveled north to sites in what is now Wisconsin, spurring the local creation of platform mounds and sculpted landscapes similar to those in the Cahokian heartland. These places were religious shrines or outposts that likely inspired the construction of more Cahokian style earthen mounds in the north.

At sites like these, Cahokian citizens embraced new places and new environments, often developing unique relationships with the communities into which they immigrated. We know this through archaeological excavations that found Cahokian-style households, site layouts, pottery and more integrated into these new communities.

It looks like they were remembering their homeland, adopting local practices while keeping their own traditions alive. In modern settings, this phenomenon is often called a diaspora – an enclave of immigrants living among local populations with their own practices and beliefs that hearken back to where they came from.

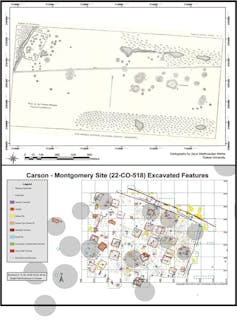

Top: Cyrus Thomas Bottom: Benny Roberts and John Connaway, CC BY-ND

For instance, at the Carson site in north Mississippi, far downriver from the Cahokian homeland, Cahokian migrants recreated familiar built environments. They constructed long, rectangular and semi-subterrenean houses at Carson that looked like home.

Decades of excavations in north Mississippi suggest that the Cahokians likely observed other people and their above-ground square houses as they migrated southward, but chose to build in ways that evoked homeland – much as how a Hindu temple in Texas still maintains the spires, domes and craftwork of India. It took another one or two hundred years for the square house style to be built at Carson.

Blending lifestyles with those they met

In northeast Florida, Cahokians encountered local communities of St. Johns people, mound builders of sites like Grant, Shields and Mt. Royal. Archaeologists call the tools and architecture of the two groups’ shared history the Mill Cove Complex.

Jayur Mehta, CC BY-ND

For instance, Cahokians may have sought unique local knowledge about the emergence of the Sun and Moon from the ocean – celestial alignments were important for Cahokians, and this would have been an unobserved phenomenon in the Mississippi River Valley. In exchange, Cahokian emissaries brought with them a kind of rock known as Burlington chert, a familiar resource for making their unique tri-lobed projectile points.

Excavations in the area revealed long-nosed god maskettes made of copper; these artifacts are found at only 20 or so sites across the Southeast and Midwest, all of which have a Cahokian presence. These masks may have been part of a hero narrative that was also depicted in rock art and narrated by Siouxan speaking groups whose traditional lands encompassed much of the Upper Midwest.

Farther north, Cahokians created other new, hybridized styles with local populations.

For example, during Cahokia’s emergence around 1050, nearby villages in the uplands of southern Illinois went through their own social transformation; they adopted some aspects of early Cahokian culture while retaining cultural and architectural features of their own.

This can be seen in artifacts found at the Halliday site, located in southern Illinois approximately 30 kilometers southeast of Cahokia; excavations have found nonlocal pottery types from Indiana and northern Mississippi, Tennessee and Arkansas, alongside pottery typical of Cahokia. People at Halliday were also eating slightly different foods than at other nearby sites, suggesting they maintained culinary traditions of their remote homelands.

Archaeologists have also found evidence that these upland villages eventually adopted a Cahokian building method that placed a prefabricated wall directly into a trench. But it didn’t happen immediately. They stuck with placing single posts into the ground to create building walls for houses from 1050 to 1350, emphasizing villagers’ choice to maintain some of their pre-Cahokian traditional practices in the face of social change.

Denise Panyik-Dale/Moment Open via Getty Images

Similarities to today

In each place where Cahokians remade themselves, they contended with local communities, as well as their individual memories of their homeland.

Cahokian migrants made houses that mimicked those at home; they built according to celestial alignments from home; and in diasporic settings, they made iconographic designs honoring mythic heroes from their homeland.

Because Cahokians never ceased making their homeland wherever they spread – albeit in unique ways in new environments – we believe it makes sense to think of Cahokian and Mississippian culture not as one monolithic entity with just one perspective, but instead, a multitude of voices that together signified something greater.

The broader anthropological implication of our Cahokian research is the reminder it provides across the centuries that migration and identity are an ongoing process by which individuals and communities make and remake themselves, all while remembering their homeland and adapting to a new one. This process describes the complexities of living in the diaspora, and it is as relevant today as it was a thousand years ago.

[The Conversation’s science, health and technology editors pick their favorite stories. Weekly on Wednesdays.]![]()

Jayur Mehta, Assistant Professor of Anthropology, Florida State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.