Five ways the Syrian revolution continues

AP/Raad Adayleh

By Wendy Pearlman, Northwestern University

Bashar al-Assad has “won” the war in Syria – or so many analysts tell us.

His regime has reconquered swaths of territory from rebel forces with starvation-and-surrender sieges, barrel bombs, chemical weapons and what one human rights investigator called “industrial scale” torture and killing of detainees.

Still, the regime might have fallen had Russia not stepped in and begun bombarding opposition strongholds in 2015.

In areas now under Assad’s grip, Syrians speak of exhaustion, forced complicity with government rule and the return of the very walls of fear and silence that they sacrificed so much to tear down.

No one should underestimate the crushing toll of this violence or overestimate the capacity of any people to endure more than Syrians already have.

“We’re tired and we can’t bear any more blood. We’re afraid for Syria,” an activist told me. And that was in 2012.

But that does not mean that the struggle for freedom, dignity and justice that Syrians launched eight years ago is over.

Since 2012, I have interviewed hundreds of displaced Syrians who championed the uprising. I have seen that their revolution persists wherever Syrians continue to believe in their capacity to make change.

Five realms of activism and resilience stand out.

1. Nurturing civil society

Forty years of dictatorships stifled independent civil society in Syria. But the years since 2011 have witnessed a flourishing of citizen-led activities in fields from education to media and the creative arts.

In Syrian towns where rebels forced the state to withdraw, communities labored to create local councils through which people governed themselves. The regime subjected these experiments in civic participation to siege and bombardment, and then collapsed them in areas retaken by its troops.

AP/ Khalil Hamra

Still, civic work continues inside and outside Syria. Citizens for Syria, itself a Syrian initiative, identifies hundreds of organizations and projects spearheaded by and for Syrians.

Among them are the Molham Volunteering Team which, beginning as a group of students, is now an essential nonprofit provider of humanitarian relief. Women Now for Development offers vocational training, literacy courses and small grants that have empowered hundreds of Syrian women.

Read more:

How the Syrian uprising began and why it matters

In these and other efforts, Syrians are demonstrating their will to build a democratic society from the bottom up, against enormous odds. This is a realm in which individual and state contributions can help.

For example, the Trump administration froze stabilization funds for Syria in 2018. That forced to a halt at least 150 civil society organizations. Some laid-off staff had no choice but to seek salaries with the only entities that offered them: armed factions, including those that the United States identified as terrorist groups.

2. Mobilizing for detainees

Syrians continue to take action on behalf of the more than 100,000 citizens who have become forcibly disappeared. Most of them were nonviolent civilians arrested arbitrarily by the government.

Copious documentation details the torture, death, rape and sexual violence synonymous with imprisonment in Syria, and even the suspected use of crematoriums to dispose of prisoners executed en masse.

Families for Freedom

Defying despair, groups such as the Caesar Families Association and the women-led Families for Freedom demand release of information about detainees and humanitarian access to detention facilities. Their mobilization, from the streets of London to the halls of U.N. and EU conferences, is keeping attention to this issue that has left few Syrian families untouched.

3. Ending impunity

Syrians are working for justice and accountability. Teams are amassing exhaustive evidence of atrocities, from photographs of prisoners’ emaciated corpses to documents incriminating leaders by name.

Several European states are using the principle of universal jurisdiction to investigate, prosecute and convict Syrian officials implicated in crimes against humanity.

In recent weeks, authorities arrested three Syrian officers in Germany and France for torture constituting crimes against humanity. And Syrian refugees submitted dossiers of evidence against Assad to the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

While state and international institutions have an important role to play, the real engine of the fight to end impunity in Syria is coming from Syrians themselves.

4. Demanding oversight for reconstruction

Assad will need hundreds of billions of dollars to rebuild the country that he played a large role in shattering.

Reports suggest that the Syrian government is already using reconstruction as “war by other means.”

For example, the Law No. 10 of 2018 proposed to give citizens limited time to register proof of ownership with the Syrian state before it would confiscate properties for “redevelopment.” Other legislation enables the regime to transfer these and other expropriated assets to private companies run by regime cronies.

AP/Hassan Ammar

Critics decry such “lawfare” as a strategy to to control society and the economy, further dispossess those forced to flee the country and enrich loyalists and foreign allies. It might also serve as demographic engineering that cleanses areas of some ethnic or religious groups and replaces them with others.

Syrian activists drawing attention to the dangerous politics of reconstruction call for transparency and accountability that were missing in the realm of humanitarian relief.

Since 2011, for example, United Nations aid programs in Syria awarded tens of millions of dollars in contracts to Assad family members and associates, thereby propping up the regime. In working against repetition of such oversight failures, Syrians continue the revolution’s fight against corruption and unfairness.

5. Building dignified lives

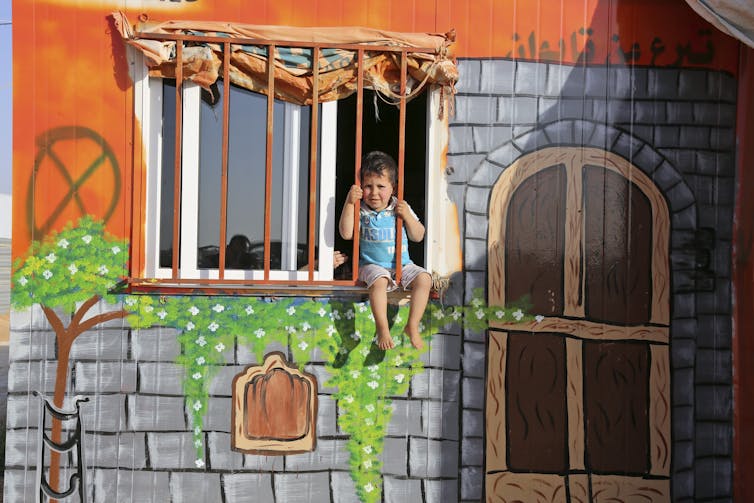

The approximately 5.6 million refugees in countries on Syria’s borders continue to work to achieve their aspirations despite severe legal and economic precariousness.

Many lack minimal access to health care and decent housing. Some 40 percent of children are not in school.

As war dies down in Syria, host states and international agencies increasingly discuss refugees’ return. The small numbers who have gone back to Syria report that they did so because they could no longer endure the harshness of life in neighboring states. Yet return is not a safe solution; already some returnees have been disappeared or killed upon arrival.

Displaced persons are eager to continue that most revolutionary act of building dignified lives, but they cannot do so unless states offer them a modicum of safety and opportunity.

Past and continuing atrocities in Syria will haunt history for generations to come. That Syrians retain any hope in a better future is not only a testament to their sheer will. It is also a sign, I believe, that the revolution they began eight years ago continues today.

Syria’s uprising did not happen in a vacuum. Read the first part of this series, “How the Syrian uprising began and why it matters,” to hear the voices of Syrians describing the oppression that characterized their lives for decades, and how they mobilized against it.![]()

Wendy Pearlman, Associate Professor of Political Science, Northwestern University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.