Think the U.S. is more polarized than ever? You don’t know history

National Archives, Timothy H. O’Sullivan photographer

By Gary W. Gallagher, University of Virginia

It has become common to say that the United States in 2020 is more divided politically and culturally than at any other point in our national past.

As a historian who has written and taught about the Civil War era for several decades, I know that current divisions pale in comparison to those of the mid-19th century.

Between Abraham Lincoln’s election in November 1860 and the surrender of Robert E. Lee’s Confederate army at Appomattox in April 1865, the nation literally broke apart.

More than 3 million men took up arms, and hundreds of thousands of black and white civilians in the Confederacy became refugees. Four million enslaved African Americans were freed from bondage.

After the war ended, the country soon entered a decade of virulent, and often violent, disagreement about how best to order a biracial society in the absence of slavery.

To compare anything that has transpired in the past few years to this cataclysmic upheaval represents a spectacular lack of understanding about American history.

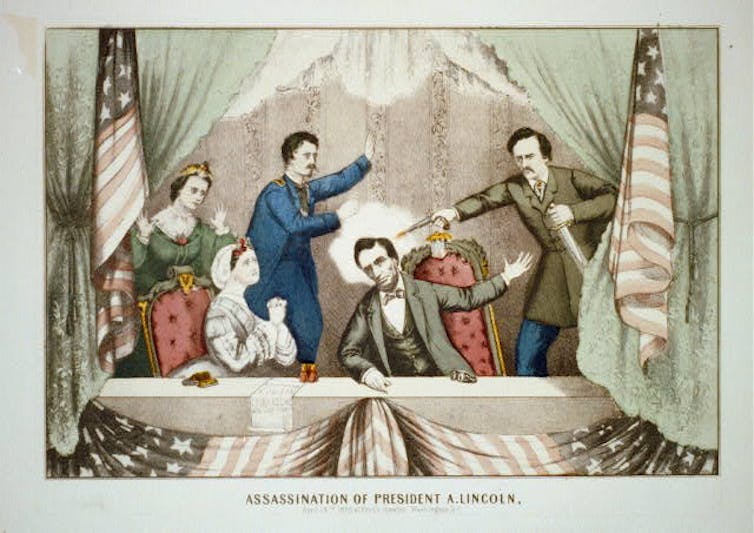

Library of Congress

Caning, secession, assassination

A few examples illustrate the profound difference between divisions during the Civil War era and those of the recent past.

Today, prominent actors often use awards ceremonies as a platform to express unhappiness with current political leaders.

On April 14, 1865, a member of the most celebrated family of actors in the United States expressed his unhappiness with Abraham Lincoln by shooting him in the back of the head.

Today, Americans regularly hear and watch members of Congress direct rhetorical barbs at one another during congressional hearings and in other venues.

On May 22, 1856, U.S. Rep. Preston Brooks of South Carolina caned Sen. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts into bloody insensibility on the floor of the Senate chamber because Sumner had criticized one of Brooks’ kinsmen for embracing “the harlot, Slavery” as his “mistress.”

Recent elections have provoked posturing about how Texas or California might break away from the rest of the nation.

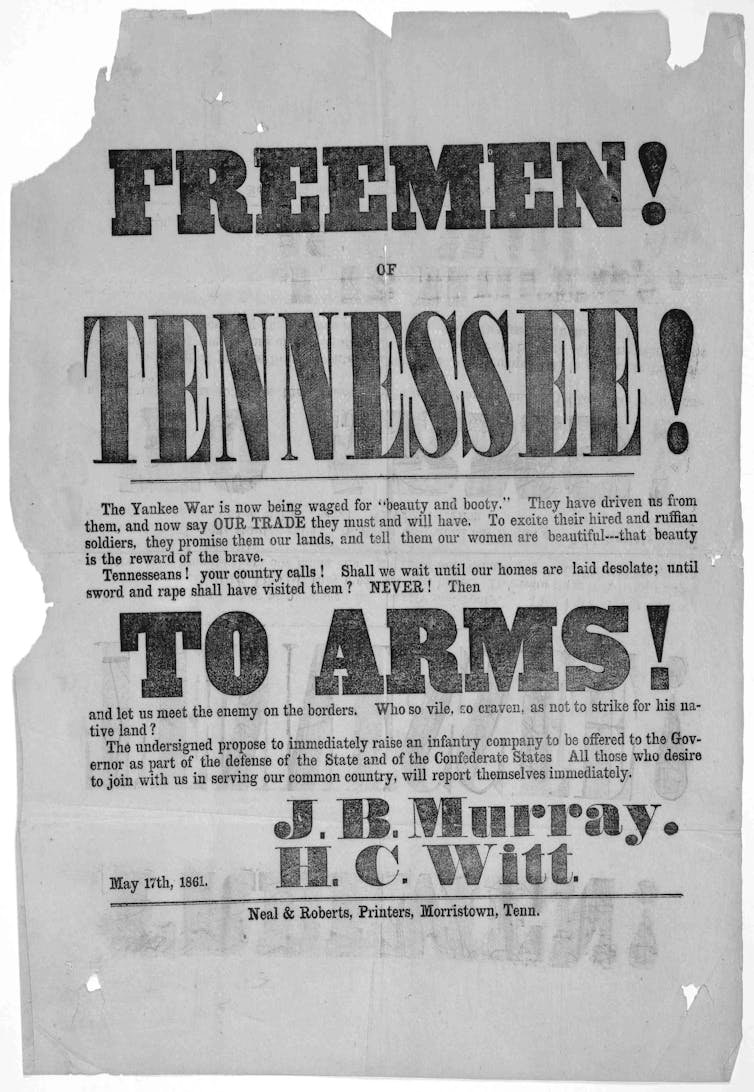

But after a Republican president was elected in 1860, seven slaveholding states seceded between Dec. 20 and Feb. 1, 1861. Four of the remaining eight slaveholding states followed suit between April and June 1861.

Library of Congress

Internal fractures, furious war

Americans were thus forced to face the reality that the political system established by the founding generation had failed to manage internal fractures and positioned the United States and the newly established Confederacy to engage in open warfare.

The scale and fury of the ensuing combat underscores the utter inappropriateness of claims that the United States is more divided now than ever before.

Four years of civil war produced at least 620,000 military deaths – the equivalent of approximately 6.5 million dead in the United States of 2020.

The institution of slavery – and especially its potential spread from the South and border states into federal territories – was the key to this slaughter because it provoked the series of crises that eventually proved intractable.

No political issue in 2020 approaches slavery in the mid-19th century in terms of potential divisiveness.

Gary W. Gallagher, John L. Nau III Professor in the History of the American Civil War, Emeritus, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.