The Trump administration has made the U.S. less ready for infectious disease outbreaks like coronavirus

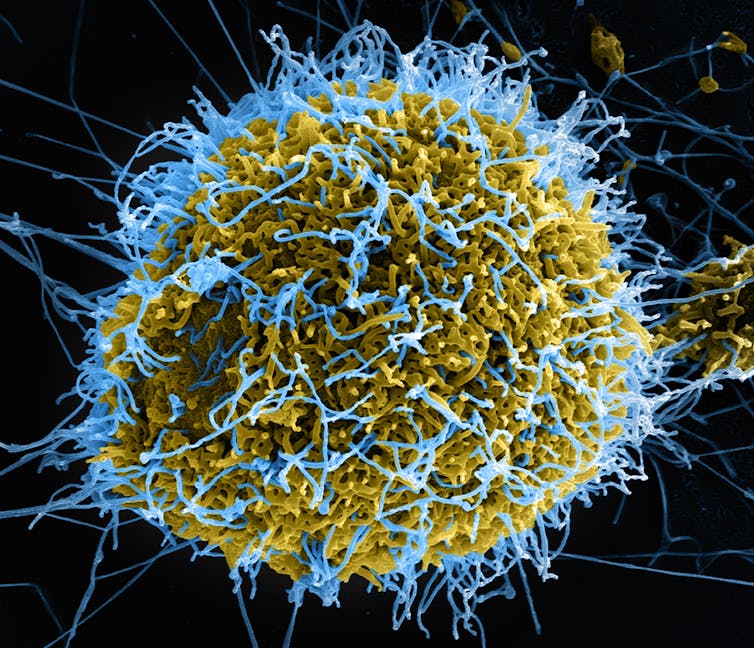

NIAID, CC BY

By Linda J. Bilmes, Harvard Kennedy School

As coronavirus continues to spread, the Trump administration has declared a public health emergency and imposed quarantines and travel restrictions. However, over the past three years the administration has weakened the offices in charge of preparing for and preventing this kind of outbreak.

Two years ago, Microsoft founder and philanthropist Bill Gates warned that the world should be “preparing for a pandemic in the same serious way it prepares for war”. Gates, whose foundation has invested heavily in global health, suggested staging simulations, war games and preparedness exercises to simulate how diseases could spread and to identify the best response.

The Trump administration has done exactly the opposite: It has slashed funding for the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and its infectious disease research. For fiscal year 2020, Trump proposed cutting the CDC budget by US$1.3 billion, nearly 20% below the 2019 level.

As a specialist in budgeting, I recognize that there are many claims on public resources. But when it comes to public health, I believe it is vital to invest early in prevention. Starving the CDC of critical funding will make it far harder for the government to react quickly to a public health emergency.

CDC

Cutting funds and staff

Every year since taking office, Trump has asked for deep cuts into research on emerging diseases – including the CDC’s small center on emerging and “zoonotic” infectious diseases that jump the species barrier from animals to humans. The new coronavirus is just the latest example of these threats.

The CDC’s program focuses on infectious diseases ranging from foodborne illnesses to anthrax and Ebola. It manages laboratory, epidemiologic, analytic and prevention programs, and collaborates with state and local health departments, other federal government agencies, industry and foreign ministries of health.

In 2018, Trump tried to cut $65 million from this budget – a 10% reduction. In 2019, he sought a 19% reduction. For 2020, he proposed to cut federal spending on emerging infectious and zoonotic diseases by 20%. This would mean spending $100 million less in 2020 to study how such diseases infect humans than the U.S. did just two years ago.

Congress reinstated most of this funding, with bipartisan support. But the overall level of appropriations for relevant CDC programs is still 10% below what the U.S. spent in 2016, adjusting for inflation.

Even worse, in 2018 the administration disbanded its own global health security team, which was supposed to make the U.S. more resilient to the threat of epidemics. This unfortunate decision was part of a reorganization that former national security adviser John Bolton carried out shortly after arriving at the White House.

Bolton eliminated the National Security Council’s global health security and biodefense directorate, and reshuffled its team of world-class infectious disease experts. In response, two highly respected leaders in the field – Rear Admiral Tim Ziemer, the NSC’s senior director for global health security and biodefense, and Homeland Security adviser Tom Bossert – left the White House.

Under Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, Ziemer had served as the U.S. point person for a coordinated global anti-malaria campaign that helped reduce deaths from the disease by 60% over 15 years. In 2016 he estimated that funding initiatives to reduce malaria generated a 36 to 1 return on investment because it averted so many deaths and debilitating illnesses.

In 2018 Ziemer was instrumental in fighting the reemergence of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of Congo, traveling there and working with public health officials to reduce the spread of the dreaded disease.

A clear and present danger

There is no wall high enough to keep virulent pathogens from crossing national borders, and when they emerge there is a potential for widespread illness and death. Containing the first major Ebola epidemic in 2014-2016, which killed 11,000 people in West Africa, required an enormous global effort. Only 11 patients were treated for Ebola in the U.S., but that was because President Obama took the threat seriously, appointing an “Ebola czar” to coordinate U.S. preparedness and assistance.

Now that the White House has evicted the NSC’s global health security experts, it is not clear who in the Trump administration will be responsible for coordinating U.S. efforts in the event of a global pandemic.

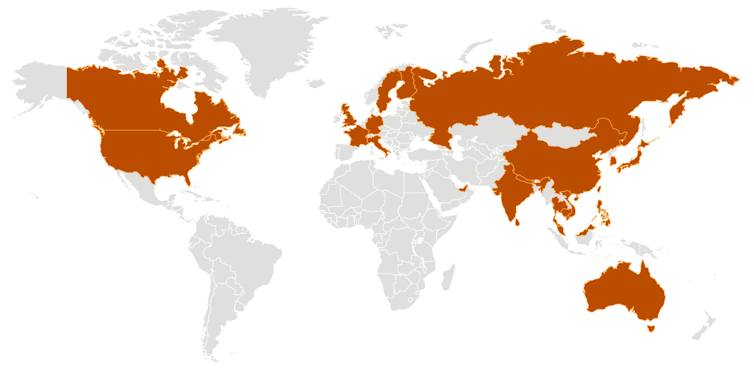

The new coronavirus that emerged in Wuhan, China, has already spread to 25 countries. The CDC has confirmed that person-to-person transmission has occurred in the U.S. It will take a large-scale effort to contain this outbreak, and battling the virus requires money.

NIH, CC BY

Although the Gates Foundation and other charities give away billions of dollars to promote public health, such gifts are no substitute for the kind of specific, targeted scientific research into emerging diseases that the CDC and other federal agencies are uniquely designed to conduct. Fighting epidemics also requires planning to prepare and coordinate with hospitals, medical professionals, pharmacies, airlines, local government and the general public, which also requires funding.

President Trump recently signed a $738 billion dollar defense budget – the highest level since World War II. It creates a new Space Force and funds research into dozens of remotely possible military threats. Relative to defense spending, the $6.5 billion CDC budget is tiny. But as I see it, deadly global pandemics and emerging biological and viral threats pose an equal or greater threat to our national security.

As climate change warms the Earth, thousands of long-frozen dormant diseases are defrosting. And the World Health Organization reports that 75% of all emerging pathogens over the past decade are zoonotic diseases, most of which are understudied. As Bill Gates warned in 2018, “If history has taught us anything, it’s that there will be another deadly global pandemic.” I believe the U.S. must allocate more resources to research, detection and global prevention and communication efforts, not less.

Linda J. Bilmes, Daniel Patrick Moynihan Senior Lecturer in Public Policy and Public Finance, Harvard Kennedy School

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.