Packaging generates a lot of waste — now Maine and Oregon want manufacturers to foot the bill for getting rid of it

iStock via Getty Images

By Jessica Heiges, University of California, Berkeley and Kate O’Neill, University of California, Berkeley

Most consumers don’t pay much attention to the packaging that their purchases come in, unless it’s hard to open or the item is really over-wrapped. But packaging accounts for about 28% of U.S. municipal solid waste. Only some 53% of it ends up in recycling bins, and even less is actually recycled: According to trade associations, at least 25% of materials collected for recycling in the U.S. are rejected and incinerated or sent to landfills instead.

Local governments across the U.S. handle waste management, funding it through taxes and user fees. Until 2018 the U.S. exported huge quantities of recyclable materials, primarily to China. Then China banned most foreign scrap imports. Other recipient countries like Vietnam followed suit, triggering waste disposal crises in wealthy nations.

Some U.S. states have laws that make manufacturers responsible for particularly hard-to-manage products, such as electronic waste, car batteries, mattresses and tires, when those goods reach the end of their useful lives.

Now, Maine and Oregon have enacted the first state laws making companies that create consumer packaging, such as cardboard cartons, plastic wrap and food containers, responsible for the recycling and disposal of those products, too. Maine’s law takes effect in mid-2024, and Oregon’s follows in mid-2025.

These measures shift waste management costs from customers and local municipalities to producers. As researchers who study waste and ways to reduce it, we are excited to see states moving to engage stakeholders, shift responsibility, spur innovation and challenge existing extractive practices.

Holding producers accountable

The Maine and Oregon laws are the latest applications of a concept called extended producer responsibility, or EPR. Swedish academic Thomas Lindhqvist framed this idea in 1990 as a strategy to decrease products’ environmental impacts by making manufacturers responsible for the goods’ entire life cycles – especially for takeback, recycling and final disposal.

Producers don’t always literally take back their goods under EPR schemes. Instead, they often make payments to an intermediary organization or agency, which uses the money to help cover the products’ recycling and disposal costs. Making producers cover these costs is intended to give them an incentive to redesign their products to be less wasteful.

The idea of extended producer responsibility has driven regulations governing management of electronic waste, such as old computers, televisions and cellphones, in the European Union, China and 25 U.S. states. Similar measures have been adopted or proposed in nations including Kenya, Nigeria, Chile, Argentina and South Africa.

Scrap export bans in China and other countries have given new energy to EPR campaigns. Activist organizations and even some corporations are now calling for producers to become accountable for more types of waste, including consumer packaging.

What the state laws require

The Maine and Oregon laws define consumer packaging as material likely found in the average resident’s waste bin, such as containers for food and home or personal care products. They exclude packaging intended for long-term storage (over five years), beverage containers, paint cans and packaging for drugs and medical devices.

Maine’s law incorporates some core EPR principles, such as setting a target recycling goal and giving producers an incentive to use more sustainable packaging. Oregon’s law includes more groundbreaking components. It promotes the idea of a right to repair, which gives consumers access to information that they need to fix products they purchase. And it creates a “Truth in Labeling” task force to assess whether producers are making misleading claims about how recyclable their products are.

The Oregon law also requires a study to assess how bio-based plastics can affect compost waste streams, and it establishes a statewide collection list to harmonize what types of materials can be recycled across the state. Studies show that contamination from poor sorting is one of the main reasons why recyclables often are rejected.

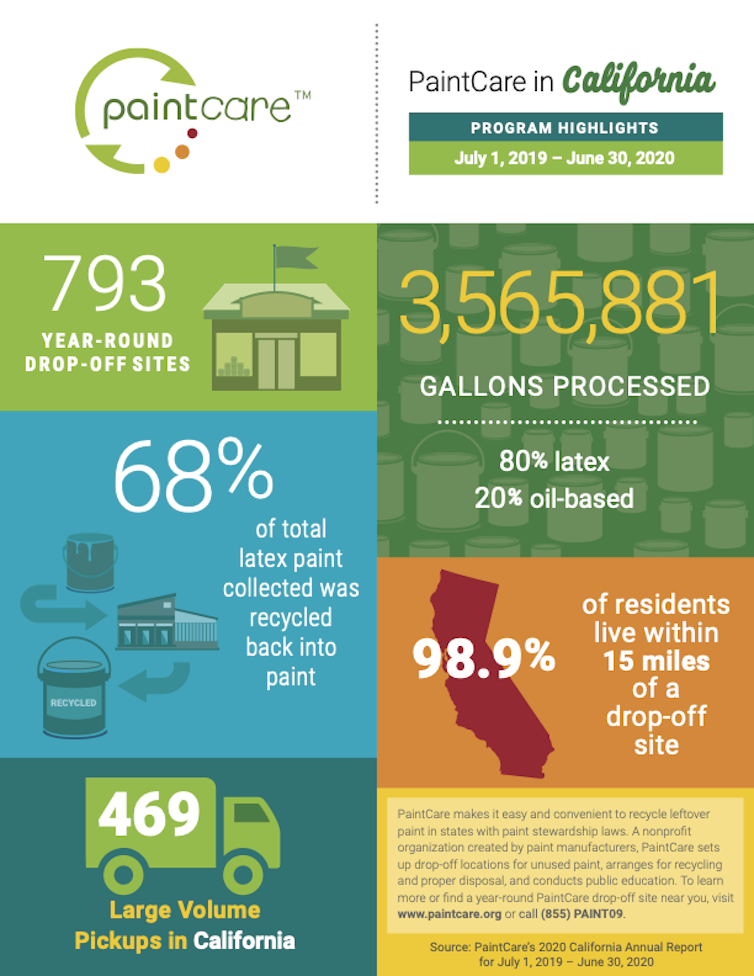

PaintCare

Some extended producer responsibility systems, such as those for paint and mattresses, are funded by consumers, who pay an added fee at the point of sale that is itemized on their receipt. The fee supports the products’ eventual recycling or disposal.

In contrast, the Maine and Oregon laws require producers to pay fees to the states, based on how much packaging material they sell in those states. Both laws also include rules designed to limit producers’ influence over how the states use these funds.

Will these laws reduce waste?

There’s no clear consensus yet on the effectiveness of EPR. In some cases it has produced results: For instance, Connecticut’s mattress recycling rate rose from 8.7% to 63.5% after the state instituted a takeback law funded by fees paid at the point of sale. On a national scale, the Product Stewardship Institute estimates that since 2007 U.S. paint EPR programs have reused and recycled almost 24 million gallons of paint, created 200 jobs and saved governments and taxpayers over $240 million.

Critics argue that these programs need strong regulation and monitoring to ensure that corporations take their responsibilities seriously – and especially to prevent them from passing costs on to consumers, which requires enforceable accountability measures. Observers also argue that producers can have too much influence within stewardship organizations, which they warn may undermine enforcement or the credibility of the law.

Few studies have been done so far to assess the long-term effects of extended producer responsibility programs, and those that exist do not show conclusively whether these initiatives actually lead to more sustainable products. Maine and Oregon are small progressive states and are not major centers for the packaging industry, so the impact of their new laws remains to be seen.

However, these measures are promising models. As Martin Bourque, executive director of Berkeley’s Ecology Center and an internationally known expert on plastics and recycling, told us, “Maine’s approach of charging brands and manufacturers to pay cities for recycling services is an improvement over programs that give all of the operational and material control to producers, where the fox is directly in charge of the hen house.”

We believe the Maine and Oregon laws could inspire jurisdictions like California that are considering similar measures or drowning under waste plastic to adopt EPR themselves. Waste reduction efforts across the U.S. took hits from foreign scrap bans and then from the COVID-19 pandemic, which spurred greater use of disposable products and packaging. We see producer-pay schemes like the Maine and Oregon laws as a promising response that could help catalyze broader progress toward a less wasteful economy.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]![]()

Jessica Heiges, PhD Candidate in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, University of California, Berkeley and Kate O’Neill, Professor of Global Environmental Politics, University of California, Berkeley

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.