When a chief justice reminded senators in an impeachment trial that they were not jurors

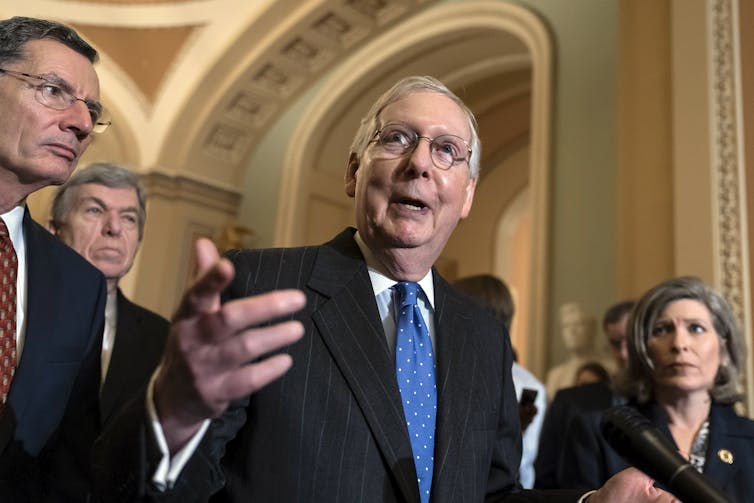

AP/J. Scott Applewhite

By Steven Lubet, Northwestern University

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell created a predictable stir when he told Fox News host Sean Hannity that he would structure the impending impeachment trial of President Donald Trump in “total coordination with the White House counsel’s office.” He added, “There will be no difference between the president’s position and our position as to how to handle this.”

This outright rejection of neutrality drew immediate protests from Democrats. Rep. Val Demings (D-Fla.), who may well be one of the House impeachment managers in the Senate trial, called for McConnell’s recusal, saying “No court in the country would allow a member of the jury to also serve as the accused’s defense attorney.”

House Judiciary Committee Chair Jerry Nadler (D-N.Y.) likewise slammed “the foreman of the jury” for saying he would “work hand and glove with the defense attorney.”

Demings and Nadler made a valid point, but they used the wrong analogy. Senators at an impeachment trial are not the equivalent of a jury and they are not held to a juror’s standard of neutrality.

AP/J. Scott Applewhite

Harkin’s objection

The principle, that senators are not jurors in the traditional sense, was well established at the outset of the 1999 impeachment trial of President Bill Clinton.

Tasked with delivering an opening statement for the House Managers – who present the House’s case to the Senate – Rep. Robert Barr (R-Ga.) reminded the senators of Clinton’s tendency to “nitpick” over details or “parse a specific word or phrase of testimony.” To Barr, the conclusion was obvious: “We urge you, the distinguished jurors in this case, not to be fooled.”

That was the moment Sen. Tom Harkin, an Iowa Democrat, had been waiting for.

“Mr. Chief Justice,” he said, addressing William Rehnquist, who was presiding over the trial, “I object to the use and the continued use of the word ‘jurors’ when referring to the Senate.”

AP/Joe Marquette

Harkin had prepared well, basing his argument on the text of the Constitution, the Federalist Papers and the rules of the Senate itself.

He explained that “the framers of the Constitution meant us, the Senate, to be something other than a jury.”

Instead, Harkin continued, “What we do here today does not just decide the fate of one man. … Future generations will look back on this trial not just to find out what happened, but to try to decide what principles governed our actions.”

Chief Justice weighs in

The Chief Justice sustained the objection.

“The Senate is not simply a jury,” he ruled. “It is a court in this case.”

Rehnquist thus admonished the House Managers “to refrain from referring to the Senators as jurors.” For the balance of the trial, they were called “triers of law and fact.”

Rehnquist and Harkin got it right. Article III of the Constitution provides that “Trial of all Crimes, except in Cases of Impeachment, shall be by Jury,” and for good reasons.

AP Photo/APTN)

In an ordinary trial, the jury’s role is generally limited to fact-finding, while the judge determines the scope and application of the law. In an impeachment trial, however, the Senate itself has the “sole power” to decide every issue.

Recognizing the Senate’s all-encompassing responsibility, and his own limited role, Chief Justice Rehnquist referred to himself throughout the proceeding only as “the Chair.”

As the U.S. Supreme Court has put it, impeachment presents a “political question,” in which all of the “authority is reposed in the Senate and nowhere else.”

Oath or affirmation required

McConnell, the Senate’s leader, has more leeway and far more power than any juror or even a jury foreperson.

The Constitution’s only procedural limitation is the requirement in Article I that the senators be placed under “oath or affirmation.”

Although the Constitution does not specify any particular wording (unlike the presidential oath, which is included word-for-word), the Senate adopted rules for impeachment trials in 1986 requiring each senator to affirm or swear to do “impartial justice according to the Constitution and laws.”

“Impartial justice” does not demand the enforced naiveté of jury service, which would be impossible in an impeachment trial. For example, the senators all have prior knowledge of at least some of the facts, and several of them are currently vying to run against Trump in 2020, while others are backing his reelection campaign.

But the Senate’s oath of impartiality clearly calls for at least some commitment to objectivity. Thus, the problem with McConnell’s announcement was not that he failed to behave like a juror.

Rather, he has declared an intention to disregard the Senate’s prescribed oath, which was fixed long ago by the very body that elected him its leader.

When Tom Harkin disclaimed a juror’s role at the Clinton trial, his purpose was not to affect the outcome of the case, but rather to underscore the full scope of the Senate’s decision-making responsibility. In contrast, Mitch McConnell appears to have boldly renounced open-mindedness itself on the impeachment court, whether as juror, judge or “trier of law and fact.”

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]![]()

Steven Lubet, Williams Memorial Professor of Law, Northwestern University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.